The Turkish word ‘gecekondu’ translates as ‘put at night’, describing a settlement (understood as a home or a neighbourhood) built illegally overnight by its inhabitants. The gecekondu can be viewed as a form of incremental housing due to the additions made by inhabitants over time, at both the scale of the home and neighbourhood. One cannot distinguish the gecekondu itself from its process. In fact, the term gecekondu both defines the home itself, as well as the neighbourhood. Despite the demolition of most original ‘gecekondu’ homes, and in their place the construction of multi-storey concrete structures, the neighbourhood is still referred to as a ‘gecekondu’.

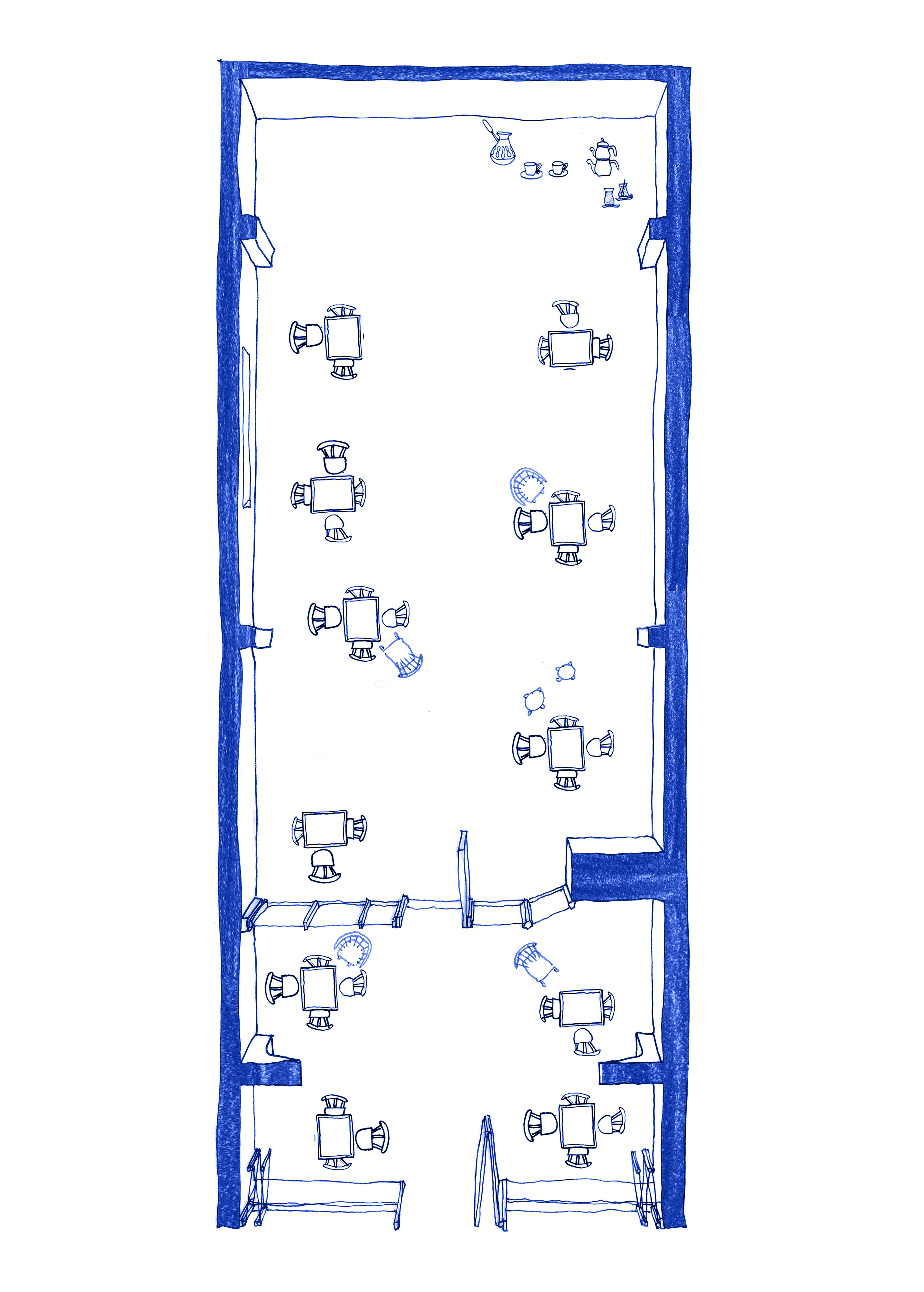

Today, the Kiraathane is essentially a humble coffee-house, frequented by a homogenous demographic of working-class retired men. Interpreted as a Third Place, they litter the streets of more working-class neighbourhoods, as well as the gecekondu. Despite its beginnings as a diverse hub of the intellectual elite in the Ottoman times, bringing Jews and Armenians together with Turks, there has since been a cultural and demographic shift in the Kiraathane. Many Istanbulites view it as a place to ‘waste time’, yet for many it is essential in the settling of oneself within their new neighbourhood, as with in the gecekondu.

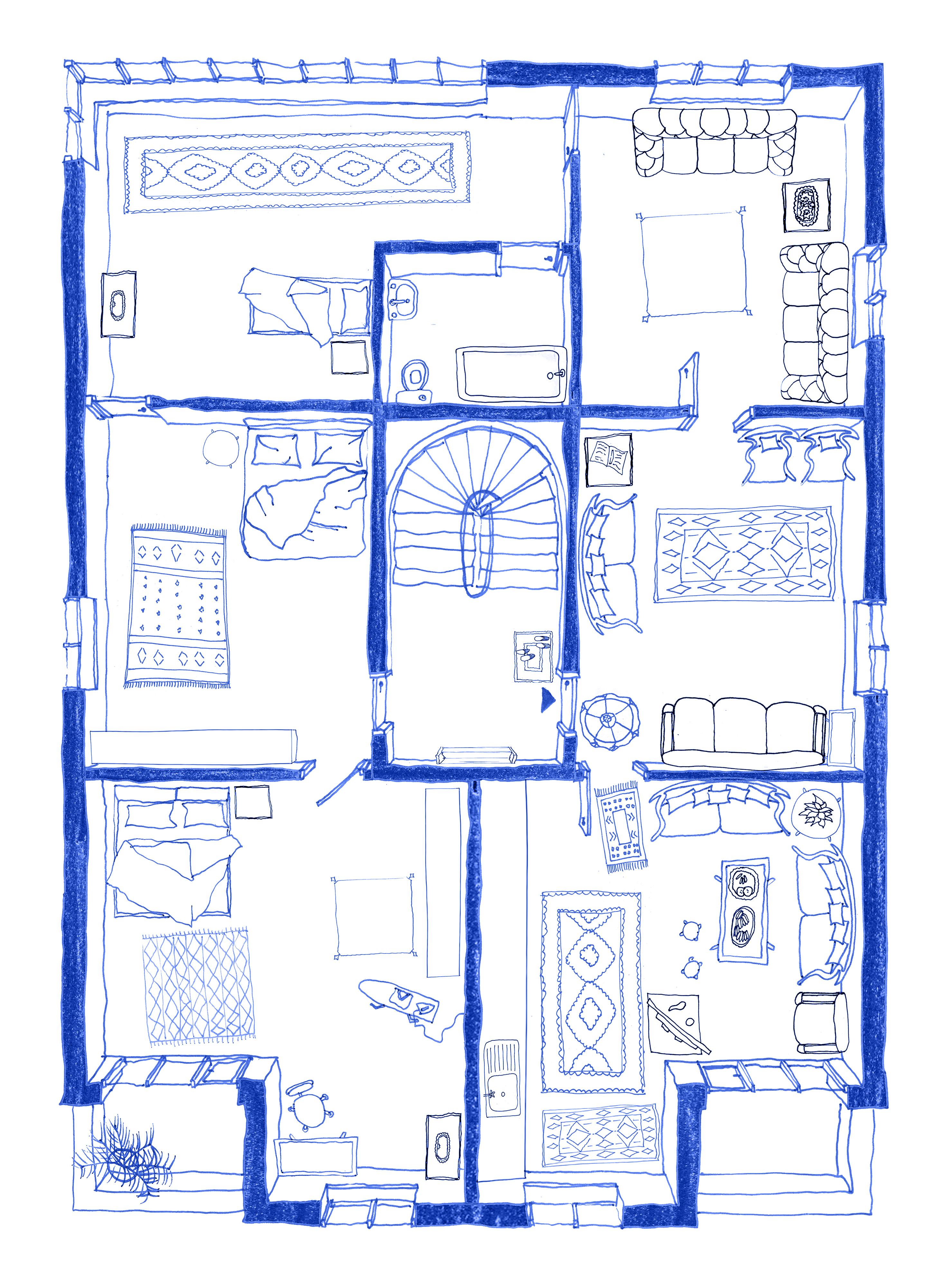

Altin Gun translates as ‘Day of Gold’ and describes the weekly meetings of an organised Gun ‘group’; often 6-12 married women. The name derives from the tradition of women pooling their resources in the form of golden coins, and in turn, sharing these at each meeting. The group is always intimate, consisting of childhood friends, neighbours, or relatives, and is based on trust, solidarity and reciprocity. Interpreted as a Third Place for Turkish Women, the Altin Gun differs from the men’s Kiraathane, as it is acted out behind closed doors.

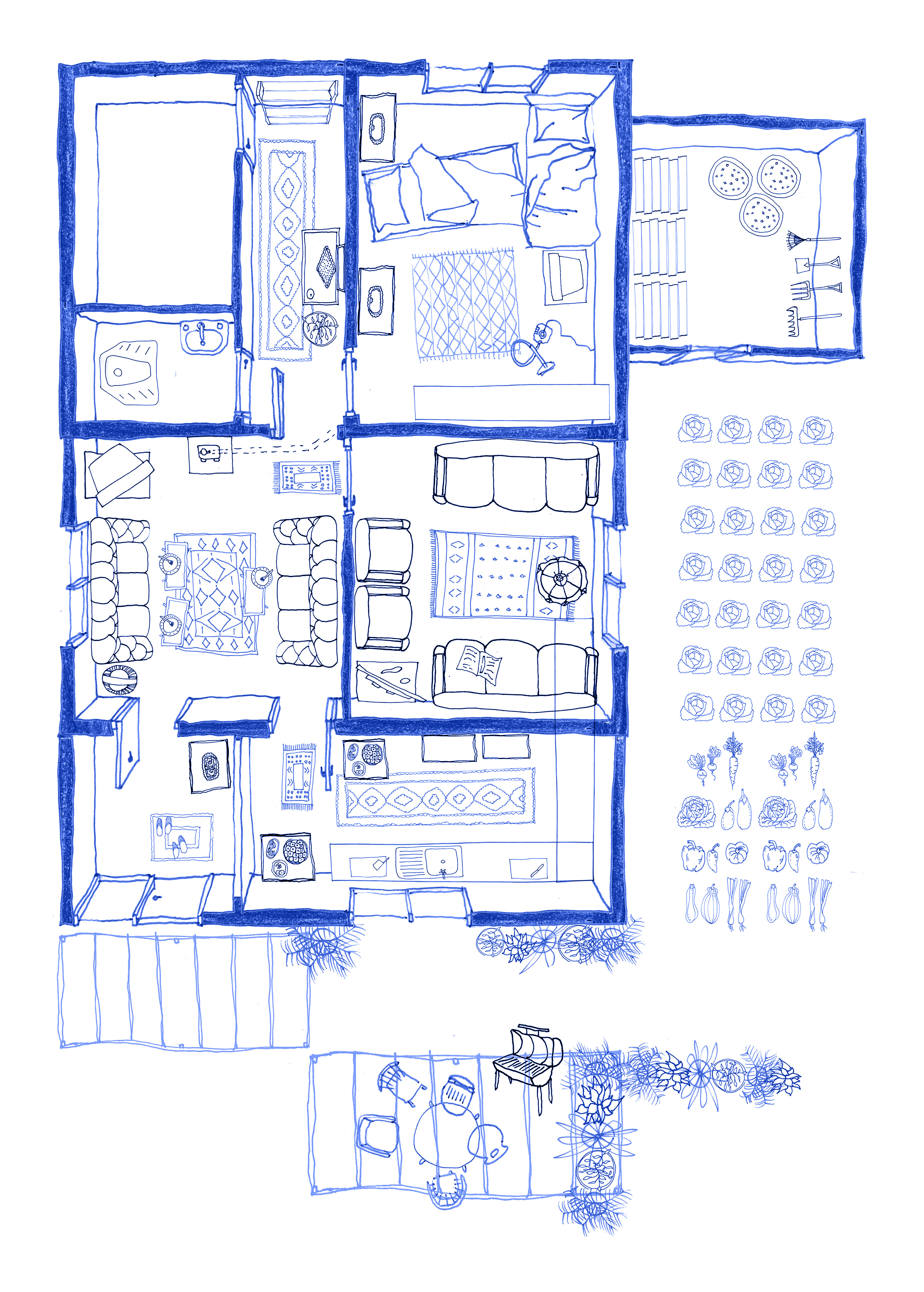

Translated as ‘Build-Sell’, Yap-Sat refers to a construction process prolific in Turkey: that of a land-owner engaging a small-scale contractor to construct a four- or five-storey block of apartments upon their plot. Specific to the deal, the units are split between the land-owner and the contractor, allowing each to gain rental income alongside housing; bolstering many into the middle-classes. Since the 1950s, this development model rapidly transformed the Turkish city, increasing density and homogeneity in the urban fabric. However, nowhere more so than the gecekondu, where the legal land ownership granted to inhabitants by the Amnesty Laws of 1983/4 encouraged the spread of Yap-Sat, and hence the ‘apartmentisation’ of once low-rise neighbourhoods.